WWOOFing in Sicily

categories: europe travel

The working day doesn’t start too early at La Casa delle Acque, a small organic orange farm at the foot of Mount Etna in Sicily. It’s around 8 O’clock. The sun has lit up the snow on the dome of the great volcano and the first pools of light have highlighted the yellow flowers that dot the orange groves. The first of the 12 WWOOFers, volunteer farmers, are trickling into the spacious kitchen of the pastel red farmhouse. The hoods of their sweatshirts are pulled up, a weapon against the cold they’ve accumulated in their bones after another night in the drafty outbuildings of the farm. They are from Austria, Spain, Belgium, Germany, Scotland, and even the US. And there’s me, escaping from the world of heated offices and flat-screen computers for that of soil and rough working gloves. We huddle closely around a long wooden table hugging cups of steaming coffee and chatting in a mixture of English and Italian.

The rather arcane acronym WWOOF stands for World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms, a concept that first evolved in the UK in the 1970s but has seen a real boom in popularity in recent years. As a wwoofer you toil unpaid in the fields for a number of hours a day and in return, you get food and board at the farmhouse.

Sicily

This farm in Sicily belongs to a squat farmer called Nirav who is sitting at the head of the long wooden table. His face is lined by 30 years of work as a sailor and by the faint hint of childhood acne. His kindly sparkling eyes suggest, even at this hour, a permanent state of semi-amusement. On his head he is wearing, like a crown, a red skull cap embroidered with elephants. Nirav was born and raised in Sicily, but his love of India is evident not just from his adopted name, but also from his passionate interest in ecology and communal living. Over the course of a year, he shares his home with over a hundred young people who immerse themselves for a few weeks, or even a few months, in a sustainable world where the energy is solar-powered, everything is recycled and the fields are irrigated by a homemade natural waste recycling system purified by stalks of bamboo.

The drive to the farm, up from the concrete jungle, of Catania, shows just how unique Nirav’s farm really is. Everywhere rubbish lies rotting by the roadside. The streets leading to the farm from the nearest town of Paterno are piled high with torn black-sacks, leaking their putrefying waste on the asphalt where it is picked over at night by packs of mangy dogs. Packaging is thrown out of the windows of passing cars and the road down by the river under the farm is blocked by dismantled kitchen parts and discarded nappies. Sicily, away from the tourist brochure glamour, is the island that the ecological movement seems to have largely passed by. “Sicilians are always the slowest to accept new ideas” complains Nirav, “We are ten or fifteen years behind Tuscany.”

Today at breakfast in the oasis of La Casa delle Acque, Nirav is complaining that Sicily hasn’t had a proper winter for five years. December was warm and the WWOOFers swam in the sea in mid-January and now the type of blood orange called sanguinelli, which traditionally ripe for picking in April are already falling off the trees in February.

WWOOFers

In the short term at least, that unseasonable weather suits the WWOOFers just fine. Despite the frigid nights, daytime temperatures reach a balmy 20 degrees – T-shirt weather. “That’s why we can’t leave,” says Martin, a Scottish graphic designer who has been here since early December. “What’s not to love here?” He and his girlfriend Fran, have quit well-paid jobs in London to travel the world. They started WWOOFing down Italy since the early Autumn, but they got stuck here in Sicily, where life plods by in snail-paced chaos. “It’s perfect here,” smiles Martin. Week after week the couple postpones their onward journey as the rural rhythm saps them of ambition. And because WWOOFing costs next to nothing, they have already extended their career break plans from 18 months to two full years. Martin says he was never a great disciple of organic food but was interested in seeing where the food that ends up on our plates comes from. “I mean it’s just so much work, isn’t it? From the planting to the picking to the transportation. And then it’s there in our supermarkets as if by magic; and we don’t even think about it.”

Working on a farm is not everyone’s idea of an escapist holiday. It has its picturesque moments such as in standing in terraced groves picking tarochi oranges, famed to be the color of the lava from Etna, with that great volcano peering over your shoulder as you snip away with the secateurs. It’s fun too collecting fresh eggs in the crisp mornings from the cackling poultry, geese, chickens and guinea fowl and it’s charming to shepherd the two languid donkeys, Heidi and Peter, back to their stables. But agricultural life has its less romantic side too. Organic irrigation systems smell of sewage, which is essentially what they are, and crowding around a table in the barn for hours on end sorting the oranges by size and quality – (“Questa buona. Questa non!”) is monotonous drudgery. After long afternoons of sorting, I dreamed at night of drowning under an avalanche of misshapen citrus fruit. Other tasks can be muscle-sapping like hauling the full crates of oranges on to a pickup truck, lugging stones around to build a new terrace or clearing a seemingly never-ending forest of bamboo sticks and shredding them in an angry machine.

Communal Living

But, as a break from your everyday life, the attractions of WWOOFing go far beyond the mere toiling of the soil. The experiment of communal living is a welcome and refreshing jolt out of our social comfort zones. Meeting people from different countries and different backgrounds and living at close quarters with them requires a series of painless compromises and minor tolerances and little moments of patience. The farming, the cooking and the cleaning all demand teamwork, volunteering impulsively to lessen a new friend’s workload. The process makes you feel better about yourself as you begin to feel more generous towards others.

And then, of course, there is the crowning moment of communal living: sitting outside in the warm lunchtime sunshine, squashed elbow to elbow around a giant wooden table while you share a home-cooked lunch made from ingredients freshly plucked from the garden. It’s a pleasure that you can’t buy at any hotel. Each lunchtime, cooked by a different chef, we feasted on vegetarian dishes based on giant green broccoli, delicious fennel, and the Sicilian red cauliflowers; all of these whisked from the soil to the plate in under an hour and with a taste that is incomparable to anything you might find in a supermarket. “We may be poor,” goes the old farmers’ proverb, “but at the table, we’re rich.”

Around that communal lunch table of WWOOFers, it’s likely you’ll find some colorful characters. WWOOFing, which inherently involves veering away from the mainstream and sometimes feels a bit like “dropping out lite”, attracts the eccentric minded. I met conspiracy theorists, idealists, doubters of modern medicine, seekers of yogic enlightenment, I met some dedicated foodies and many more WWOOFers who just want to get away from the rush of modern life and, on limited funds, spend winter in the sun-kissed countryside of a faintly exotic foreign country. Martin, one of the latter, was worried that La Casa delle Acque, with its solar panels and meditation room, might be too idealistic for him. But he need not have worried:

“No-one preaches and no-one tries to convert anyone. You’re a vegetarian? That’s cool. You’re not? That’s cool too.”

Patrick

Then there are the truly eccentric like Patrick, from Ireland, a firm believer in ghosts who says he has ‘retired’ from the IT industry. Cheerful and generous he has a winning chuckle and he has been at Casa delle Acque for almost half a year now. He has no plans to leave and finally, he has finally determined to pick up some Italian by taking advantage of an EU sponsored language course in Paterno. Every afternoon he drives the few kilometers there and back to take beginner’s lessons with a well-meaning but disorganized middle-aged teacher who seems to have a crush on him. Her lesson plans range from understanding the menu to discussing gay adoption and the pair of them spend much the time arguing in his broken and mispronounced Italian and her atrocious English about the best way to cook the organic broccoli.

Patrick drives back in the dark in a beat-up old wreck of a car that he has driven down from London. Only one of its lights work and then only works on full-beam so he considerately switches it off when a car comes from the other direction, driving along in the pitch blackness, the flanks perilously close to the wall, as he coughs out of the window. His main dream in Italy is the quixotic quest to find some porridge oats, which, in a bark of a voice, he pronounces ‘parridge’ to the local Sicilian shop-keepers who, deeply alarmed, direct him to the nearest pharmacy. When, over another sunny lunch, he announced dead-pan to the assembled company that he was planning to start up an orange farm in Ireland, no-one knew whether or not he was joking.

Paterno

Paterno is a gritty, blue-collar sprawl of concrete tenements and grim-looking streets; the side of Sicily you won’t find in the tourist brochures. In the rain, its rubbish-strewn outskirts look almost apocalyptical with pot-holed crumbling walls of half-derelict factories. If it looks like the set of a gangster film, that’s probably no coincidence. Paterno was once an axis of the infamous Mafia ‘triangle of death’ of the 1970s. Even in the rural idyllic of the orange groves the shadowy presence of organized thuggery is palpable. Near certain groves, you’ll see grim-looking men parked by the side of the road who, it’s said, offer their services, for a fee, to “watch over” the local farmers’ oranges, an offer that few dares to refuse. The main occupation of these grizzled and scruffy looking men seems to be to sit there smoking and looking grumpy while others work. On Sundays, unimpeded by the local police, illegal horse races are held. Dozens of cars are parked along the road, bets are exchanged, and petrified horses attached to carts are whipped into gallops against the clock on the hard, unforgiving asphalt.

Yet even those tawdry and pitiful spectacle’s make up the fascination of WWOOFing. With the farms away from the well-trodden path of tourism (you’ll rarely see a tripper in Paterno) you can see a country with its heart out and sometimes its pants down. I arrived back from Sicily without seeing a single touristic point of interest. Instead of sipping cappuccinos in Renaissance squares, I found myself, on my way to chop down a tree, downing espressos in petrol stations. I was exhorted to try local sweet-cakes by the woman behind the till while discussing fuel prices and bunga-bunga with a diminutive Sicilian farmer. It’s far from glamorous, but somehow priceless.

Perhaps WWOOFing is the perfect 21st-century break for my post-backpacking generation, a generation that has seen (and photographed) so much and understood so little. It’s micro-tourism – getting to know a small patch of the world intimately – and during your stay, it’s easy to forget the rest of the world exists. I’ll come back with course hands and tired muscles but still refreshed.

Will I continue to eat better, live more ecologically, and be more patient and tolerant? Well, that’s an entirely different story.

2 Responses to “WWOOFing in Sicily”

Leave a Reply

Tags: article, italy, sicily, volunteer travel, wwoof

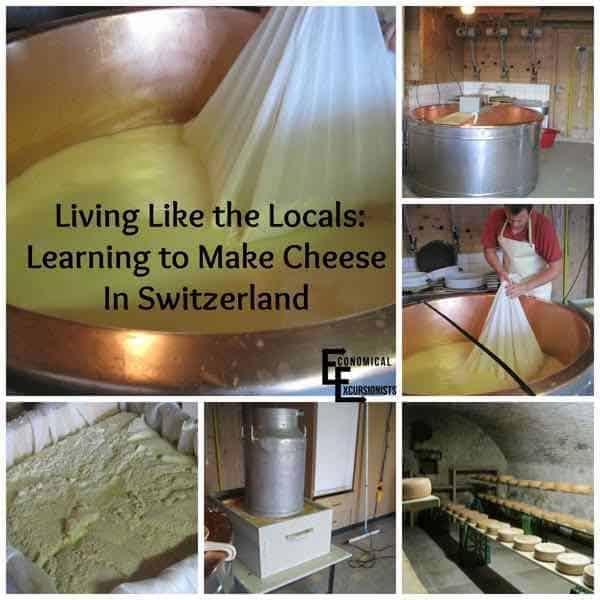

WWOOFing – Learning to Make Cheese in Switzerland

WWOOFing – Learning to Make Cheese in Switzerland Travel to Sicily in Italy – Episode 197

Travel to Sicily in Italy – Episode 197 Travel to Sicily – Episode 651

Travel to Sicily – Episode 651 Travel to the Piedmont Region of Italy – Episode 662

Travel to the Piedmont Region of Italy – Episode 662

Daniel Trumino

Says:October 11th, 2015 at 10:02 am

Hi I’m interested in working at niravs farm can some one provide me he’s contact email please ? Kind regards

Sarah Robbins

Says:March 25th, 2024 at 7:04 am

We live in Toronto Canada and planning our 2 weeks visit (first time for me) to Sicily April 14-28, I came across your charming article accidentally and enjoyed it fully.

You write beautifully.

My husband and I have our sailing boat ( Benatou 44) in Greece for the last 10 years, where we spent most summers while he was teaching. Now that he is retired we like to spent spring and fall sailing.

This year we are meeting sailors friends in Sicily, however we wish to do land exploration of Sicily.. more inland than beaches.

We had experienced woofing in NZ and Australia and loved it ..

we are not planning woofing in Sicily but would love to get your recommendations for non tourist travel.. to see, meet and learn about the Sicilian farming.

Thanks a bunch,

Sarah Robbins